Background

The Malayan Railway was the only transport system providing nationwide public rail in the early 60s. Its lines ran from Singapore up the west side of the central mountain chain to the Malayan-Thai frontier, and from Gemas through the East Coast States to Kota Bharu and Tumpat in Kelantan. In addition, the Malayan Railway Administration owned the Port Area and was responsible for the operation of Port Swettenham, the principal mainland port in the Federation as well as the minor ports of Port Weld, Port Dickson and Teluk Anson. Port Swettenham handled cargo annually amounting to over one and a quarter million tons and major development of the port was then being undertaken.

The passenger traffic carried in a year exceeded seven million persons. Goods traffic carried has exceeded two and a quarter million tons for several years. The Malayan Railway Central Workshop at Sentul was large and well equipped, employing over 2,000 representative of almost every skilled trade. A new wagon shop was completed at Sentul and modernisation of the Railway was on its way. High performing Malayan officers have been sent abroad since 1947 for training on special courses and to obtain professional qualifications. The total personnel employed number nearly 14,000 which included Malayans of all races in the Federation. The importance of the Malayan Railway to the present and future economy of Malaya and to the well being of a large section of industrial peace can therefore hardly be overstated.

The Railway was a Public Statutory Body and the equity in the Railway was vested solely in the Federal Government. The General Manager, Malayan Railway derives his authority from the Railway Ordinance, 1948 which has made the General Manager a Corporation Sole by the name of the Malayan Railway Administration and gave to him the “power and authority generally to execute and do all such acts, deeds and things as may be necessary or proper to the control and working of the Railway and other services ancillary to the Railway.” A Railway Board and a Port Swettenham Board with non official and official representatives would advise the General Manager on any matter relating to the administration and working of the Railway or of the Port respectively and whom he was bound to consult on certain matters specific in the Railway Ordinance. He may not act in opposition of these Boards without the authority of the Minister.

The Minister of Transport has direct power of the General Manager on any matter except appointments, promotions and disciplinary control where power was under the jurisdiction of the Railway Services Commission. Railway accounts were also liable to scrutiny in the Parliament. The Malayan Railway Administration could not raise funds for capital development or borrow money itself but must look to Government to provide funds if it could not meet requirements from its own resources.

The question of the status of Railway Servants has been the subject of much correspondence then. It was not entirely clear even to the Government in 1951 whether the servants of the Railway were to be treated as Government servants or as part of an entirely independent entity. The Management, however, continued to hold the view that Railway Servants appointed by the General Manager were employees of the General Manager and that the terms of their employment were matters for negotiation between the General Manager and Railway servants. But the view of many Railway employees themselves was that they were Government Servants and that their conditions of service were a matter for negotiation between Government and themselves. They considered, and many hold this view that the Railway was a Government Department.

On the other hand, the Solicitor General advised in 1958 that Railway Servants were not subject to the General Orders of Government. The Staff side, arguing from the premise that Railway employees were Government Servants, claimed that Government circulars and General Orders should automatically apply to them and that it was wrong that the General Manager should have the power to modify them when applying them to his staff. At the same time, the laws of the Federation except where otherwise expressly provided, applied to them in the same manner as they applied to Government Servants and

“ any person in the service of the Railway Administration shall except where otherwise expressly provided by any other written law, be deemed to be also in the service of the Government of the Federation”.

As such, Railway Servants were also deemed to be public servants for the purpose of some parts of the Penal Code, but this of course did not make them servants of the Government of the Federation.

The situation was not of little importance. Many Railway employees suffered from a sense of grievance that their conditions of service especially in the matter of retirement benefits were not the same as those of the servants of the Government of the Federation. There was perhaps a feeling that the Railway should be subsidised as required from the Government Revenues, in the same manner as other Government Departments which were not run on commercial lines. This was not however, the way the Malayan Railway Administration saw it. For them, the Railway was a public service to be run on commercial lines which was expected to pay its way. It is obvious that the fundamental differences in the point of view of the Malayan Railway Administration and its employees derived from their divergent interpretation of the status of the Railway has caused not only psychological disturbances but led to much unnecessary argument, dispute and industrial unrest.

The Event

On 24th December 1962, 14,000 railwaymen throughout the country stopped work after the Ministry of Labour failed to bring amicable settlement between the Malayan Railway Administration and the Railwaymen’s Union of Malaya dispute. The last train left Kuala Lumpur at 3.57 pm while all the night mails were cancelled. What started as a paralysis of the railway then became a catastrophe of the country’s whole economy. The Federation’s ports were virtually closed and the Singapore Harbour Board and the Penang Port Commission have declared their inability to handle cargo originally destined for Port Swettenham. Cargoes for Malaya were being unloaded at distant ports such as Saigon, Hong Kong and Colombo. Thousands of cases of tinned milk and thousands of bags of flour were abandoned at Calcutta because of the railway strike which had affected Port Swettenham. All rail services in the two territories including the international coach to Bangkok have been cancelled until further notice.

The President of the Railwaymen’s Union of Malaya (RUM), Mr Donald Uren had given 14 days notice for the strike to occur on Christmas Eve. The reason why both sides were at odds were strikingly parallel to the pay fight between British Railways and its employees. The British Government was unwilling to increase the wages of workers in an industry that was losing money. The workers argued that a man should be paid fairly for the job he does, regardless of the employer’s profits.

It was the same story with the Malayan Railway. The railway worked to deficits rising from over $1 million in 1948 to about $4 million in 1952, earned surpluses falling from $3.5 million in 1953 to $1.7 million in 1956, worked again at a deficit from 1957 to 1961 when it showed a surplus of $1.75 million thus succeeded in clearing the cummulative deficit of $2.45 million.

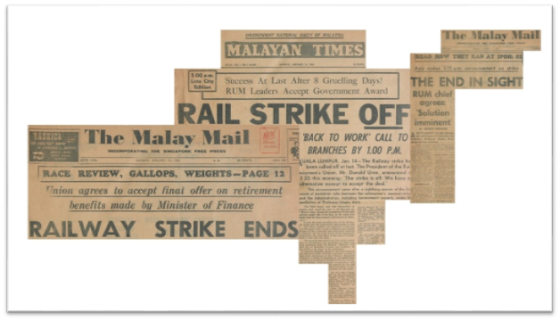

Ungku Aziz Newspaper Collection

RUM formed in 1960, demanded :

i. The placing of all daily-paid staff on a monthly basis with an additional four days’ pay, making 30 days.

ii. Granting a four increments to all monthly paid staff other than the clerical service.

iii. Vision of the port clerical and railway miscellaneous clerical service schemes to bring them in line with the Government’s state clerical scheme.

The 32 day strike brought Malaya’s rail services to a grinding halt. Professor Ungku Abdul Aziz, then the head of the Economics Department, University of Malaya stepped in as the role of mediator. On 7th January, the green signal calling off the 17 day old rail strike was expected to be given at any time following efforts by Ungku Abdul Aziz. The talks lasted all day on the 6th and continued until the early hours of the next day. Before discussions at the University of Malaya began, both the Union and management fulfilled their goodwill pledges. The workers called off pickets outside the Kuala Lumpur Railway Station and the Administration ripped off the barbed wire fencing outside its building which has been declared a protected place. Ungku Aziz who made a surprise call at the administration building to ensure the wire fencing came down was loudly cheered by the strickers. They then broke into song with “For he’s a jolly good fellow.” From midnight until early in the morning, Ungku Aziz dashed between the two conference rooms occupied by the Railway Administration officials and members of the RUM. However, the marathon came to an end at 6.30 am as Ungku Aziz came out of the conference room looking tired and dejected with the announcement that he had given up hope of a settlement. Uren said that eventhough Ungku Aziz has done a first class job and took great pains, the offers were unreasonable and unsatisfactory. The strikes continued and pickets were out again.

On the 18th day, Tengku Abdul Rahman stepped in and immediately made considerable concessions to everyone in the railway sevices. His statement said, “I met Professor Ungku Aziz and members of the Administration together with the Deputy Prime Minister, Tun Abdul Razak and several other Ministers at the Residency”. Talking about the new proposal, Tengku added, “This proposal must be considered a very big concession indeed in view of the fact that daily rated workers will get 27 times their pay on conversion to monthly rates”. With Tengku’s intervention, hopes rose again and Ungku Aziz said in a statement that at the Prime Minister’s request, he has resumed mediation on the basis of new offers.

On January 14th 1963, Ungku Aziz reported that he had just finished a 75 minute conference with officials of the Railwaymen’s Union of Malaya. Earlier, there had been a 10-hour session of talks at the University. At 3.15 am after Ungku Aziz had made his statement, the President of RUM, Mr Donald Uren said he agreed with it. Just before 4 am, Ungku Aziz rang the Finance Minister, Mr Tan Siew Sin, and told him the RUM had agreed to accept the final proposals made by Mr Tan on retirement benefits the day before.

The railway strike ended on 16th January 1963 with the first passenger train between Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and Penang to start running on Wednesday morning. The epic strike ended after midnight with the arrival of the finance Minister, Mr Tan Siew Sin, Transport Minister Dato Sardon bin Haji Jubir and Labour Minister, Enche Bahaman bin Samsuddin at the University. Mr Packrisamy, General Secretary of RUM signed the agreement on behalf of the RUM and Dato Ahmad Perang, GM of Malayan Railways. A special codeword was flashed to the RUM branches all over the country to be transmitted to workers who have been anxiously waiting the message since Malayan Times and Radio Malaya first announced the news that agreement had at last been reached and that the strike was off.

On January 22, the Railway Administration and the Railwaymen’s Union of Malaya signed a six page agreement to end the strike. Wage increases under the agreement will cost the administration an additional $2 million a year.

Mr Uren, RUM President (left), Prof Ungku Aziz (middle) & Dato Ahmed bin Perang, General Manager of the Malayan Railways (right)

The union obtained :

- Pay rises for 5,400 monthly paid staff averaging $15 each, the highest being $140 for a limited number of special grade technicians and the lowest $6. An average of two increments.

- Conversion of 8,600 daily-rated workers to monthly basis at the rate of 27 days. Also improved provident fund benefits, annual leave and medical benefits.

- Railway Provident Fund contributions to be increased from six to eight per cent.

- An undertaking by the administration not to employ anyone on a casual basis other than at Port Swettenham.

Dato Ahmed bin Perang, General Manager of the Malayan Railways apologised to the public for the inconvenience caused to them by the strike and expressed the hope that the administration and the staff would return to work and start working as a team, striving to repair the damage and enable the railway to play its full part in developing economy of the country.

Such was the magnitude of the strike which was said to be the longest and largest in the country so far. Eventhough it happened fifty years ago, much improvement and progresses have been made over the years in the working conditions of not only the Railway workers (now known as KTM) but the workers in other sectors as well. Nowadays, it is practically unheard of for employees getting daily wages for fulltime jobs. Two important points to note here is that first, this episode has involved our renowned Professor DiRaja Ungku Aziz where he was praised by the Prime Minister for working tirelessly and unselfishly without any time or thought for sleep or food to settle the strike situation and that second, the events leading to the end of the strike took place at our very own University of Malaya.

Notes written by,

Zanaria Saupi Udin,

from the Ungku Aziz Collection, Za’ba Memorial Library

References

- Federation of Malaya (1961). Report of the Commission to enquire into disputes between the Malayan Railway administration and its employees. Kuala Lumpur : Government Press.

- Malayan Railway: 100 Years 1885 – 1985. (1985). Kuala Lumpur: Amw Communications.

- Sanders, J. O. (1947). Railways report for the period 1st April to 31st December, 1946. Kuala Lumpur: Malayan Union Government Press.

- Ungku Aziz Newspaper Collection 1961-1963, Za’ba Memorial Library.